Close Reading Strategies Across the Grades

In the past, close reading was a strategy reserved for high school and college students (think back to the days of highlighting your college textbooks), but the introduction of Common Core State Standards (CCSS) has the strategy trickling down to middle school and elementary classrooms as well.

By using close reading strategies, your students will read and reread text passages, using thoughtful analysis to gain a deeper understanding of the text with each read through. Close reading moves readers past the surface content of the passage and allows them to delve into more complex concepts, such as discussing why the author made certain word choices, analyzing themes throughout a poem, or determining how a narrator’s point of view shapes a story.

In her publication, A Close Look at Close Reading, Beth Burke, NBCT, outlines the steps that teachers can use to design a close reading lesson for their students.

- Reading #1 – Look for Key Ideas and Details

The initial reading should be as independent as possible, with little background or pre-teaching. Here, students are looking for the main ideas and details of the text and story elements.

- Reading #2 – Look at the Text Structure</strong

- On the second reading, focus your students on a smaller portion of the text that includes complex elements or ideas so they can read to gain a deeper understanding. They should focus on the author’s choices in structure, vocabulary, or patterns.

- Reading #3 – Add Your Own Knowledge and Ideas

Upon the third reading, students should begin to focus on how the text applies to their own backgrounds and experiences, and what it means to them.

Introducing Close Reading to Your Students

When practicing close reading strategies in your classroom, keep the following aspects of close reading in mind, as they support the structure of the CCSS assessments.

Reinforce college and career readiness standards and the Common Core using instructional lessons with an extended four-part lesson format.

View Product →

Short and Complex Texts

Whether a stand-alone piece or an excerpt pulled from a longer text, close reading should be practiced on short passages of two or three paragraphs to about two pages, depending on the grade level. At the same time, they should be complex passages. They should include challenging vocabulary and sentence structure. Also, look for passages that don’t always present a “right answer” to questions or discussion, but instead are open to several interpretations.

It’s also important that you provide passages from all genres of literature, including folktales, myths, biographies, poetry, short stories, scenes from plays, and primary source materials.

Limited Background Knowledge

When practicing close reading exercises, avoid any prereading discussions on the passage. The goal is to have your students approach the piece with a limited background. Frontloading takes away much of the work expected from your students. Through the repeated reading, your students can begin to fill in the background information from their own experiences.

Text-Dependent Questions

As the name implies, questions should not be so general that they can be answered without ever reading the text. Students need to rely on the text for their answers, rather than general background knowledge. Students should approach each reading and repeated reading with a specific purpose or question in mind, which will cause them to read more deeply each time.

Ensure that you are including questions that represent all of the ELA standards. They should have to revisit the text to find evidence of the author’s message, the characters’ feelings, use of language, text structure, or point of view.

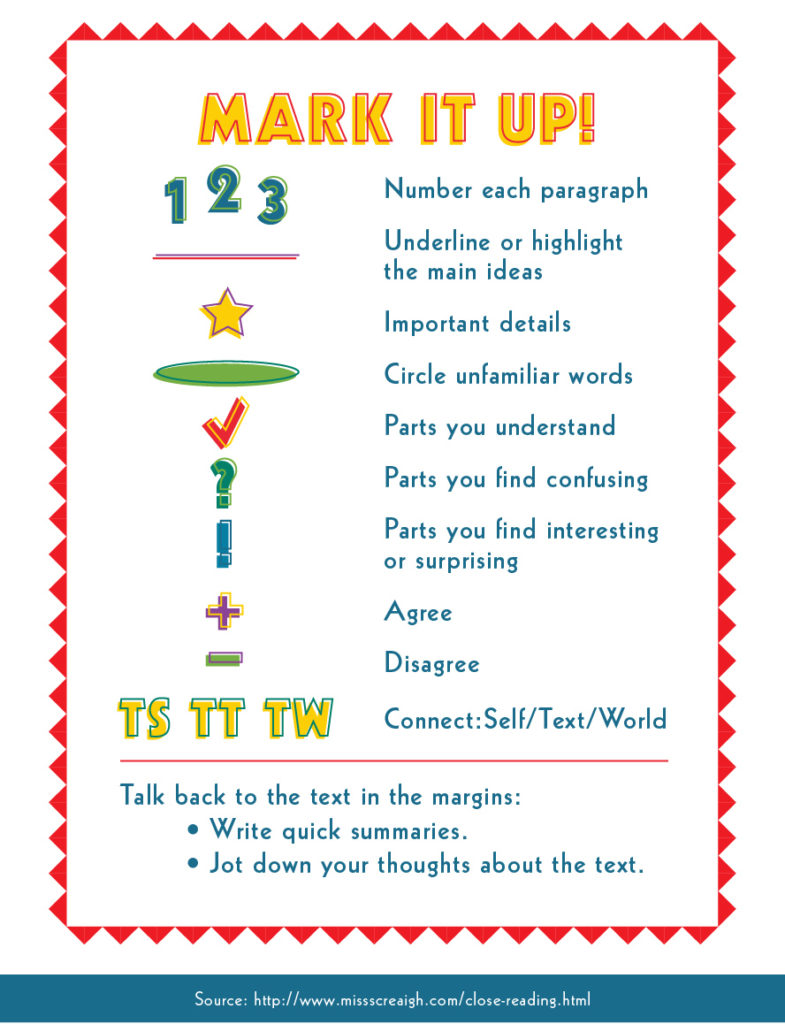

Annotation

This is often referred to as “reading with a pencil,” as students are encouraged to circle, underline, and write notes as they read through a passage. They can highlight words they are unsure of, identify patterns in the story, or call out points that back-up their ideas. Annotations can also be helpful when students need to develop written responses to questions.

Close Reading Advice for All Grade Levels

Want a little more information on how you can incorporate close reading techniques into your own classroom? We reached out to reading and language arts instructors at different grade levels to see what advice they had to offer.

Close Reading Strategies For an Elementary Classroom

Amy Saporetti, a Reading Specialist for grades K−6, stresses that working with elementary students requires a good deal of modeling when introducing close reading.

“With my reading support students, I usually model close reading through the use of a teacher think aloud. I select a portion of the text we have been reading, reread it aloud, and share my thinking about how the text works. A third rereading of the text enables me to go even deeper to understand what the text means. After modeling this procedure and practicing it as a small group, I gradually release the responsibility of close reading to my students.”

Her school has also developed a common method of annotation across all K-6 grade levels.

“During close reading, we show students how to read with a pencil.’ As students read, reread, and interact with complex texts, we teach them to annotate, or mark up, a text. In the primary grades, close reading and annotating often take place during whole group instruction. Students might gather around an enlarged copy of the text, while their teacher models close reading and annotate his/her thoughts. In the intermediate grades, students read independently, or with a partner, while annotating directly onto a piece of text.”

Below is a copy of the annotation guide that Amy and her colleagues use school-wide.

Close Reading Strategies for a Middle School Classroom

Ashley Tice is an eighth-grade English Language Arts Teacher who has discovered that her middle school readers do best when she steps out of the way and lets them read independently.

“I’m a big proponent of having students read independently. Oftentimes I find that students read a lot closer when they explore a text themselves first. I will read aloud to model tone and for stylistic effect. However, close reading is a much better tool when I assign students to read a text and analyze it in a more independent nature.”

Ashley also explains how she encourages her students to “chunk” the text for deeper understanding.

“The Common Core standards are pushing for more complex texts with higher Lexile® measures and more rigorous higher-order thinking. While I can appreciate the effort in rigor, I find that students can struggle with text complexity as the Common Core demands.

I do a lot of chunking – depending on the text. Having students read closely, even if it’s by focusing on a paragraph at a time or even sentence by sentence, allows them to grasp the basic details and topics better. A lot of times I scaffold my questioning accordingly, but mostly, I require textual evidence for textual literary analysis. By requiring this, students have to revisit the text again, sometimes even more than once, in an effort to understand what’s being asked of them.”

Close Reading Strategies for a High School Classroom

Kelly Brosig, a tenth-grade English Teacher, uses close reading in her class to help her students support a prompt with text-based evidence. She outlines the three-step process she uses when leading her class through close reading practice.

“The first read is to get the basic meaning, the second read is to look for details and literary devices, and the third read is for thematic connections, symbols, style, etc. To encourage close reading, I do a variety of activities including handouts/questionnaires, class discussions, or forums to get the students looking for deeper meaning and literary devices.

Right now, we are working on finding and analyzing text evidence in tenth grade, so students can use the text to support a prompt. One may assume that high school students can read, so therefore they can do this already, but many students struggle with reading to find basic comprehension. Sometimes they can’t read a passage independently, so that is when oral reading and audiobooks come in handy. If they can get a basic understanding of the text, then we can do some higher-order analysis.”